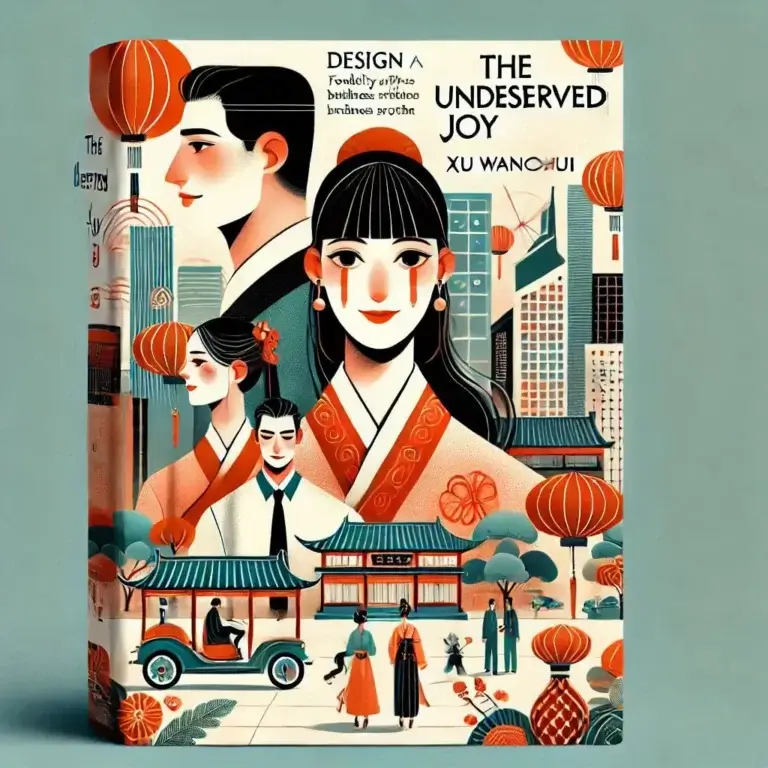

Chapter 8 Theme: Have you seen the program list for the Bolo Mid-Autumn Festival gala? Content: [program list.jpg] Qi Shejiang is going to perform crosstalk with Meng Jingyuan??? 1L: ????? 2L: ????? As a fan of this face, I can’t believe it! 3L: Am I crazy, or are Bolo and Qi Shejiang crazy? No, it’s Xia Yiwei who’s gone crazy, right? 4L: What the heck, I never expected Qi Shejiang’s line “I plan to perform crosstalk next” to be true! Qi Shejiang, such a tough guy! 5L: A werewolf +1, I can’t believe I’m thinking about how Uncle Meng will support Qi Shejiang… 6L: I’m done for, as a fan of this face, I’ve never watched crosstalk before, but I’ll wait to see it for Jesse!! 7L: Bolo Media is amazing!! Anyway, I will definitely wait to see the show! 8L: This is crazy, Qi Shejiang… does he not want to be a good idol anymore… 9L: Honestly, this program is indeed well-planned; they actually let this veteran artist support Qi Shejiang! 10L: Is this really considered support?? Letting him shoot a male lead drama would truly be support, having him perform crosstalk with Teacher Meng is just exploiting his popularity!

ReadingWorms

"Unlock the joy of reading—discover, explore, and grow with ReadingWorms!"

ReadingWorms

"Unlock the joy of reading—discover, explore, and grow with ReadingWorms!"